“We are increasingly interested in where materials come from and what their production entails from an ecological and social perspective. But it is often hard to find good information on this subject.”

—Jane Hutton “Wood Urbanism” 2019

The inclusion of wood in a landscape can provide a sense of warmth that glass, concrete, stone, and metal do not. Ipê, a tropical hardwood, has been a favored choice for designers and clients alike in outdoor applications, due to its durability. However, the cost of this wood extends far beyond dollars per board foot, at the expense of the wild places from where it is extracted—often intact forests in South America. Ipê is not grown as a plantation wood; rather, it is “hunted” in the wild. The tree’s large flowers bloom in the dry season, before their leaves have emerged, making it an easy target for harvesting. The trees are slow-growing and occur in low densities, as infrequently as one mature tree per twenty-five acres, and as many as one for every seven acres. Less valuable trees and other vegetation surrounding ipê specimens are cut as collateral damage on the path of harvest, an ecologically devastating practice.

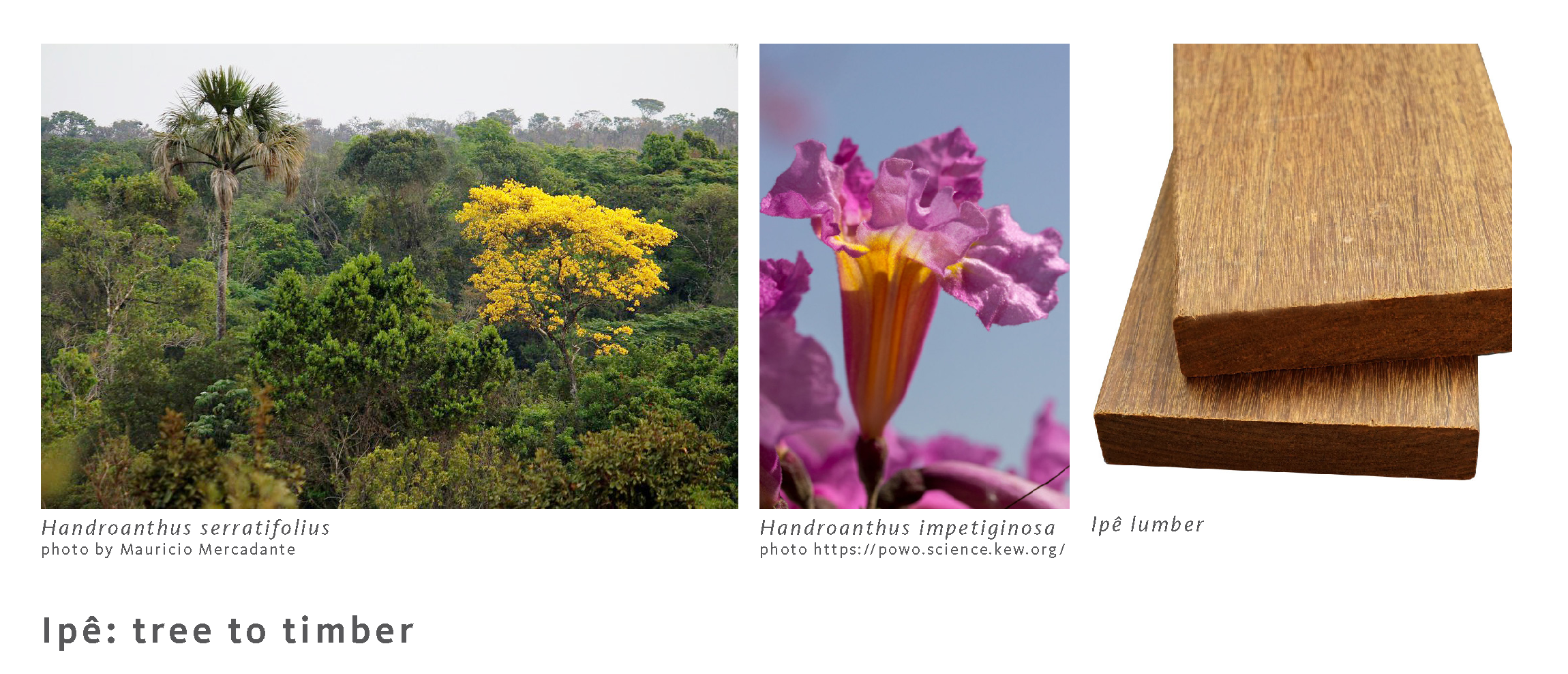

Biologically, several species are branded as “ipê” in the trade, most in the genus Handroanthus (formerly Tabebuia), including H. serratifolius, H. impetiginosus, H. chrysanthus, H.heptaphyllus, H. guayacan and, H. billbergii. While these are some of the most common Handroanthus used for timber, others, of the 35 species in the genus, are sought-after ornamental trees, incorporated into landscapes for their stunning pink or yellow blooms (dependent upon species). The number of common names is equally impressive: ipê, tajibo, lapacho, guayacan, primavera, amapola, tahuari, apache, maculís, palo de rosa, rosa morada, cortez, cortez negro, guayacán amarillo, cortés amarillo, corteza amarilla, roble, poui, pau d’arco, epay, and Brazilian-walnut. The lengthy list of names speaks to the wide distribution range and diversity of species: from Central America and Mexico through the northern extents of Chile, Argentina, and Paraguay. Recently, the common name “ipê” has been applied to other species in the trade, such as Dipterix odorata (cumaru) and Eucalyptus marginata (jarrah).

The annual Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) determines which plants are officially considered endangered and regulated. In 2022, it was proposed that the genus Handroanthus, along with the related species Roseodendron and Tabebuia, be considered for inclusion on Appendix II of CITES. It is now formally recognized that wild populations of these trees have been reduced to such an extent that continued harvesting, without regulation of trade, threatens species survival. A similar proposal in 2019 was withdrawn. Ipê (or species of Handroanthus, Tabebuia, and Roseodendron) ) are not only being extracted unsustainably, but are also difficult to differentiate from one another, especially as de-natured slabs of timber. Wood color presents a spectrum, from rich brown to a distinctly yellowish hue in a natural variety.

The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) was founded in the early 1990s after the first United Nations Earth Summit in Rio de Janiero, Brazil to prevent unsustainable forestry, monitor trade and to promote “environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial, and economically viable management of the world's forests" (in the words of the FSC online mission statement, 2022). FSC maintains a certification and labeling program that ostensibly demonstrates how timber products have met a set of rigorous management and processing standards, but this system may be less effective in practice than in aspiration. A host of critics have called timber certification greenwashing, and, more severely, likened it money-laundering.[i] Some have found flaw in the certification process that does not track individual units of wood, but rather certifies companies and forest management units. Specific points of origin for timber are hard to monitor—whether from a certified forest, or not, and the high value of ipê makes it especially vulnerable to illegal trade. FSC-certified products are often priced roughly 25% higher than uncertified wood, which covers the costs associated with maintaining certification standards for forest management, chain of custody, group certification, and fiber sourcing—the four criteria for FSC certification.

Higher commercial costs also assuage the consciences of those in distant markets; in Europe, Canada, and the United States of America, by far the largest consumers of ipê, which combined make up 85% of the demand.[ii] Once imported, the boards are primarily used for basic landscape features such as decking, fence posts and railway tracks; an inglorious end to such sparsely populated trees. In 2008, New York City’s Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability, established by Mayor Mike Bloomberg, made the first steps to curb reliance on tropical hardwoods through the publication of The Tropical Hardwood Reduction Plan. This document pledged to reduce the city’s consumption of this lumber by 20%, acknowledging the city’s contribution to global climate change and provided actionable steps to utilize more sustainable find replacement materials. The plan also offered a detailed account of wood use by the Department of Parks and Recreation and other agencies for boardwalks, promenades, marine terminals, and park benches, but it has been difficult to trace the city’s actions to achieve this commitment over the subsequent fourteen years.

Many of the proposed alternatives outlined in the The Tropical Hardwood Reduction Plan are already being tested around New York City; black locust lumber, plastic composites, concrete, and thermally treated pine, oak, and ash have all been implemented in various conditions, and each carries its own positive and negative environmental baggage (to be traced in subsequent FGS articles). Some practitioners propose new modes of engagement and investment in more sustainable forest futures. Winners of the recent competition Reimagining Brooklyn Bridge (2020) sponsored by the Van Alen Institute strategized to work with a team of scientists, conservation organizations, and community foresters employing low-impact harvesting methods in Guatemala’s Maya Biosphere Reserve. Other steps have included stricter legislation on forest commodities, such as the proposed New York Deforestation-Free Procurement Act (2021), which is currently in committee within the Senate. This bill calls for extending an existing ban on ebony and mahogany to other tropical hardwoods for government projects and for state contractors to further certify that timber products used for work are not contributing to deforestation and degradation of ecosystems; similar legislation has recently been reintroduced in California.

Ipê is not just a denatured timber commodity; the many species that go by this name are intrinsic members of diverse South American biomes and forest communities that work together to temper the global environment. Designer and homeowner demands for durable wood in outdoor applications has greatly contributed to the rampant harvesting and over-consumption of ipê and other tropical hardwoods; it is this demand that must be discouraged if we are to make a significant impact on the deforestation and destruction of critical ecosystems that is accelerating climate change.

[i] https://e360.yale.edu/features/greenwashed-timber-how-sustainable-forest-certification-has-failed, 2018.

[ii] https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Demand-for-Luxury-Decks-in-Europe-and-NA-is-Pushing-Ipe-to-the-Brink-of-Extinction.pdf.